Charlie Hunnam on ‘Papillon’, Watching His Work, and Reuniting with Tommy Flanagan

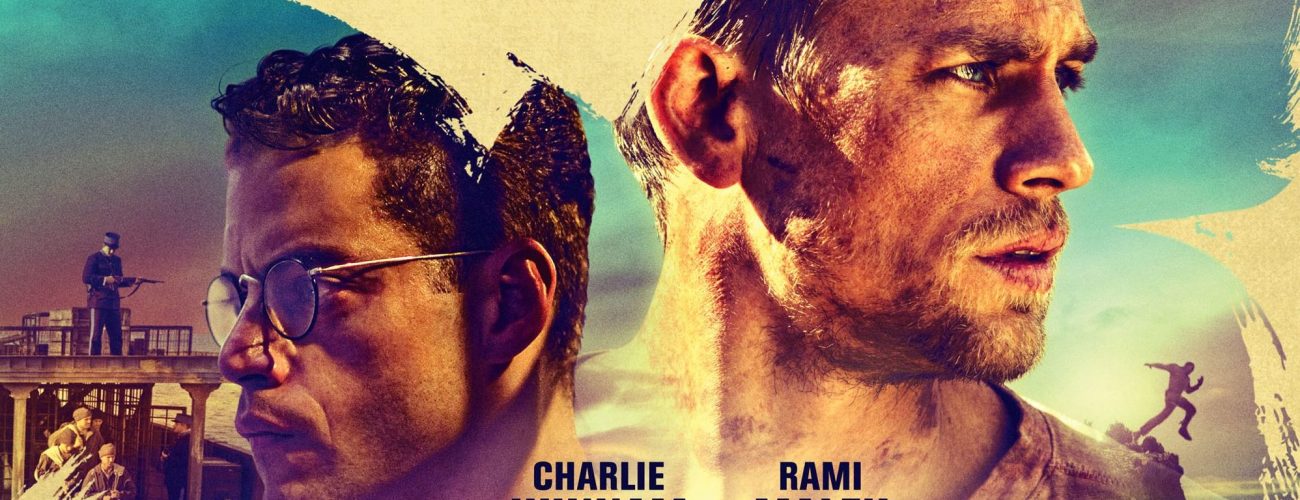

Collider.com — From director Michael Noer and based on the international best-selling autobiographical books from Henri Charrière, the prison drama Papillon follows the epic and harrowing tale of a safecracker from the Parisian underworld, known as Papillon (Charlie Hunnam, in a compelling stand-out performance), who is framed for murder and condemned to life in prison on Devil’s Island. Unbreakably determined to regain his freedom by escaping, Papillon forms an unlikely bond with convicted counterfeiter Louis Dega (Rami Malek, in an equally compelling performance), who agrees to finance what will inevitably be a harrowing escape, in exchange for his own protection.

At the film’s Los Angeles press day, Collider got the opportunity to sit down and chat 1-on-1 with actor Charlie Hunnam, who talked about partnering with Michael Noer and Rami Malek to tell this story, why he initially turned this role down, how he’s glad that he finally decided to go all in, and the part he played in getting Tommy Flanagan (Sons of Anarchy) into the film. He also talked about which of his own movies he was able to watch and enjoy, after shooting it, wanting to become more proactive by reaching out to directors that he’d like to work with, not succumbing to the gravitational pull to the culture of Hollywood, the Ned Kelly movie he recently shot with director Justin Kurzel, why it’s been such a long journey to getting some of his own material into production, and signing on to do Jungleland with director Max Winkler.

Collider: Really tremendous work in this! This seems like one of those projects where you really have to go all in, and there’s just no half-way.

CHARLIE HUNNAM: Yeah, I think that’s right. Even just the logistics of making this film required such a consistent commitment. We shot six-day weeks, and long hours. Michael and I, and Rami [Malek], too, worked very, very closely on shaping the material, so we would get together on our seventh day, for hours and hours, and figure out what we were going to do, the following week. That required a lot of rewriting, and stuff like that. It was like a fever dream experience. We just literally did nothing but work and sleep, for about ten weeks, but I had great partners. I really just came to really love Rami and Michael, so it was pretty great to have that experience with them.

With everything you went through to do this, is it something where you can look back and go, “I’m really glad I had that experience,” or do you go, “What on Earth was I thinking?”

HUNNAM: No, I’m really glad. To me, it’s just all about the process, about how I spend my time, and if I feel nourished, day-to-day. I was born a bit of an existential fuck, so I think, as we all do, that there’s an enormous amount of suffering involved in the human experience. You’ve got to figure out a way to balance the scale. When I’m working on something that I’m really excited and passionate about, I just feel deeply fulfilled. It’s why I don’t ever really like to watch a film after. I like the experience to exist in a pure way, in my mind. Watching a film breaks that spell because I look at it from the outside, as opposed to having the experience of it from the inside.

Is there anything of yours that you’ve watched, where you’ve enjoyed the experience of watching something you were in?

HUNNAM: Only ever once, and that was The Lost City of Z. I really enjoyed that. I watched it twice, [which was a mistake]. I got greedy. I had such a lovely time when I watched it the first time, and then I watched it the second time, and it was the wrong environment. I know that this is a discussed phenomenon, but I had never experienced it as acutely, how different a film can play in different environments with different audiences. It’s extraordinary. My first time seeing it, I watched it in an environment, where it was a very small group of filmmakers, and I really, really, really loved it. I got transported, and I really forgot about myself. I was just in the film. And then, I watched it again in England at a premiere at the Natural History Museum with the upper class, snobby elite of London society, and it was just an excruciating experience. It was so weird.

I know that you hesitated before signing on for this. What caused that hesitation, and what got you past that hesitation?

I know that you hesitated before signing on for this. What caused that hesitation, and what got you past that hesitation?

HUNNAM: It’s funny, it was multi-dimensional, my hesitation. There’s a long process to get a film across the line, to actually get it into production. More and more, I’ve found that since I’ve become an element that can help the financing, I see scripts in an earlier stage, and it’s always a crap shoot whether the work is going to actually be done because it’s an inexact science. There were some fundamental problems with the script, so I had misgivings about being able to fix it. That was compounded by the fact that we were putting ourselves up in a very precarious situation, remaking such a beloved film. Once a film is made, it’s just the nature of our culture that the book is irrelevant, to a certain degree. The reality lives much more weighted towards the film. You can make the very compelling argument that this isn’t a remake, he was a real man, and this is an independent adaptation of the source material, but the world is just not going to view it that way. The tricky thing for me was that I just really loved Michael [Noer]’s work, but I did initially turn it down, and another actor that I really respect took the role. It was one of the few times where I’ve really regretted turning something down. And then, it didn’t work out with that actor, and they came back to me and I ended up finding a path into it.

Do you think you would have gone to see the movie, if that other actor had stayed in it and you hadn’t done it?

HUNNAM: Yeah, I think I probably would have. I am genuinely an enormous fan of Michael’s, predating this. It’s been four or five years of very closely watching what he was doing, since his debut film came out and I saw it in the theater in London. So, yeah, I probably would have.

Had you reached out to Michael Noer, at all, to try to find something to do together, before this?

HUNNAM: No, I never had reached out. I had never been that proactive. When I worked with Guy Ritchie (on King Arthur: Legend of the Sword), he said that it had made an enormous impact on him when actors had reached out to him before. It started a relationship that had then been creatively fruitful, so he had implored me to start doing that. I only got as far reaching out to the number one on my list. I reached out to Justin Kurzel, and we ended up having a cup of coffee and really, really liked each other. I just got back, a few days ago, from Australia, wrapping a film with him. So, I’ve got to do that more often, I guess.

What is that movie?

HUNNAM: It’s a story of Ned Kelly (The True History of the Kelly Gang). It’s too early to talk about, but I think Justin is extraordinary. Snowtown is a bonafide masterpiece of filmmaking. He’s extraordinary. And honestly, that film that I just wrapped is just the best experience I’ve ever had making a film. I have high hopes that we did something special. I’m a relatively small, but significant part of it.

Did that lead to you wanting to work on your own stuff, as a writer, producer and director, or is that something you always had the idea that you wanted to do?

Did that lead to you wanting to work on your own stuff, as a writer, producer and director, or is that something you always had the idea that you wanted to do? I can’t imagine what you had to put yourself through, physically and emotionally, for Papillon, but you did such tremendous work in the film that it really paid off. Was it even more challenging, having just done it prior, for The Lost City of Z?

I can’t imagine what you had to put yourself through, physically and emotionally, for Papillon, but you did such tremendous work in the film that it really paid off. Was it even more challenging, having just done it prior, for The Lost City of Z?